By Alex Yoho, ABOM

Because eyewear is a custom product for the visual and lifestyle needs of each individual patient, communicating between the point of sale and the lab is crucial. Of course, the main communication is the order itself. This can be done the old-fashioned way with paper orders or using the modern method of electronic transfer. Either will work, but there are things to consider with each method.

Paper orders are actually turned into electronic orders at the lab via the lab’s LMS (lab management software), which means there are two opportunities for transcription errors: one from the person transcribing the doctor’s Rx, not to mention the patient’s choices, and one from the lab’s data entry person. It is possible to check the wrong box on an order form and end up with a drastically different product.

Electronic ordering is available in various forms, but usually consists of a software app provided by the lab that resides on a computer in your office. It could be as simple as a Web page that you could access from any computer, or it may be a component of your office management software. Any of these methods is immediately superior to paper orders, since what is keyed in from your office goes directly to the lab’s computer, thus eliminating one person’s transcription error potential.

A downside to the speed and accuracy of electronic ordering is a loss of personalization. When using paper order forms, we can explain things in more detail. For example, if I specify a brown #2 tint with a hint of yellow, there is not an option for that in an electronic order form. It has to be added to a note section in the order, or a phone call must be made. In either case the job is delayed in some manner and flagged for the special request. Perhaps as Artificial Intelligence is developed, it will recognize these nuances of customization that are required will be dealt with automatically, but the personal communication of this industry is what makes it enjoyable. For now, we can just know that if we do add a note, it will slow the job down a bit.

As a side note, if you have an old lab friend and are concerned that electronic ordering will put them out of a job, rest assured that this is highly unlikely. Voice or written descriptive details still require a human touch.

Eliminating transcription errors, though important, is not the end of benefits with electronic orders. The real value is in entry validation. Entry validation will not allow the order to complete if it finds conflicting information. For example, you choose your favorite progressive lens option and order it in a green polarized which is not available in that progressive. Perhaps a particular anti-reflective coating cannot be applied to a lens that has the tint that your patient wanted. In either of these situations, the program would immediately inform you that the combination is not available and will usually show the list of options that you could consider.

If you get in the habit of using the program to enter the order while the patient is there, these marvelous programs let you check availability instantly, and when you order a multifocal it won’t let you out without entering the height or anything else it knows is needed to process the job. Some pop up as reminders, such as, did you want an AR coating? If you are chatty with patients as I am, and you were talking about their mother’s cousin’s daughter having a newborn baby, well, you might just forget to ask if they want that AR coating. All of this lends itself to higher accuracy, and if the doctor enters the prescription directly into the office software, it may even feed directly as well, leaving almost no chance for error.

Most electronic ordering systems can accept a digital frame tracing device. These small tabletop units allow you to acquire the exact shape and size of the frame and send the data in with the order. For those wishing to use their old frame, this allows them to wear their eyewear while the lenses are being made. The frame tracer can also trace new frames that the patient has tried on, so the lab can get right to work on the lenses until the frame arrives, or while a new frame is on order. Otherwise, the order would often be delayed until the lab receives the frame. Speedy turnaround time makes for happy patients, and happy patients make us all happy.

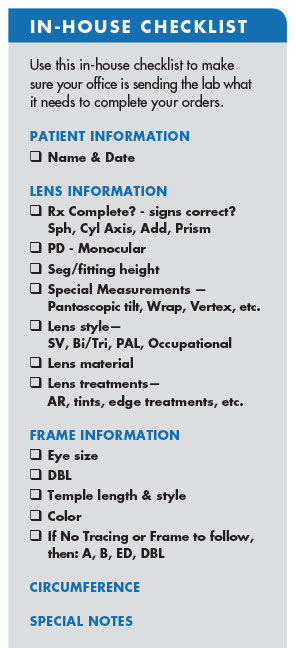

Let’s look at some things that are essential for a good working partnership with your lab, and the reasons they are important.

First, the patient’s name must be on the order. You’d think this is obvious, but you’d be amazed at how many times the patient’s name is left off. This obviously creates a delay for the lab to call and work with the dispenser to determine who the job is for. Aside from the delay, record keeping is a critical part of operations for office and lab, which makes the order date another needed piece of information.

The prescription is a given, but it always should be double checked. If possible, this double check should be done by another person. When we have written something that we have firmly in our mind, but make an error in the writing, it just doesn’t jump out at you when the wrong sign is placed before a number; an axis is left off; prism is often left off; or an add power forgotten. This can happen often, particularly in a busy office with interruptions. The prescription could be sent to the lab without a prescription at all if a frame, lens style and measurements are done prior to the eye exam—and has been. That’s an embarrassing call from the lab!

Measurements are critical to processing eyewear. Here are a few things that happen in the lab to help you understand why.

Let’s say the lab has an uncut lens that is large enough to cut the shape out. The lab must determine exactly where in the lens to cut it, and that depends entirely upon the measurements.

The patient’s PD, or interpupillary distance should be given on any job. On the lab side, the A measurement and the bridge size are needed to determine the amount to decenter the uncut lens optical center to ensure that it is directly in front of the patient’s eye horizontally. This is calculating the difference between the sum of the A measurement plus the DBL (often referred to as the “Frame PD”) and the patient’s PD. The lenses are then decentered one half that difference each. Any deviation from this will result in induced prism which, at best will create eyestrain, and at worse cause double vision. Without a PD, the lab has no information to decenter the lens before cutting to shape.

You might even include a PD on a plano sunwear job (plano eyewear does not require a PD), since it might accidentally be the only record you have of a patient’s PD. If you have a -10.00 contact lens patient with no spectacles and can’t wear their contacts, who calls you from Timbuktu saying, “Please make that pair we looked at before I left, and I’ll pick it up in three days.” Having that information on a lab order might save the day.

A fitting height (or segment height) is critical for any multifocal. Single vision lenses generally do not require a fitting height unless they are aspheric or a significant lens power, since the eye is usually positioned in the upper third of the frame which generally puts the optical center 4 to 5 mm lower than pupil center. With frames typically having 8 to 10 degrees of pantoscopic tilt, oblique astigmatism is kept within reasonable limits automatically. Progressives and lined multifocals require more precision.

When the lab receives a multifocal fitting height, they utilize the B measurement of the frame to determine how far above or below the line or reference point is placed from the center of the lens shape vertically. As late as the 1960s, if you forgot a bifocal height, you could tell the lab, “Just make it 4 below” (meaning 4 mm below the geometric center) and you would be reasonably safe since the frames were smaller and generally centered vertically. With today’s larger styles, however, the eyes are often higher than center, and “4 below” would just be ridiculous.

Today’s lenses, particularly the newer digitally surfaced designs, require more precision to eliminate the distortions intended. If the fitting height is not communicated well, they could perform worse than an average normal lens. This brings up some of the newer measurements that are required for the newer freeform designs. Other position of wear measurements such as pantoscopic tilt, vertex distance and others are now needed for the lenses to perform as designed. These are typically taken with electronic measuring devices that feed data directly through electronic ordering software which becomes nearly mandatory as we begin to use more of these designs.

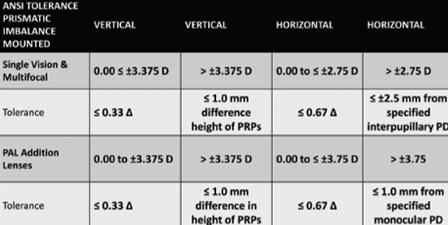

There are misunderstandings with these lenses as well. Since lens designers understand the effective changes that occur when a lens position is different from the refracted position, lenses are manufactured to a different prescription to compensate for the positional difference. When the lens is checked in from the lab, and the prescription reads differently than the doctor ordered, it is sometimes rejected as being out of ANSI tolerance. Obviously, this would lead to a discussion between the office and the lab for explanation.

Situations like this are not all bad. This particular example would give the lab an opportunity to explain that ANSI Z80.1 – 2005 states, “If the manufacturer applies corrections to compensate for the as-worn position, then this corrected value must be stated in the manufacturer’s documentation. These tolerances then apply to the corrected value.” Consequently, a lab choosing to comply with ANSI standards should be supplying the “as-worn” prescription on the paperwork that accompanies the lenses, and the office should be aware that the lenses should read in at the compensated Rx, instead of the doctor’s written Rx.

It seems the more things change in this industry, the more opportunities there are for growing in knowledge with one another. Learning about our industry and how things work is what makes things interesting to me. Labs have been in the education business since the beginning, and it takes many forms.

It seems the more things change in this industry, the more opportunities there are for growing in knowledge with one another. Learning about our industry and how things work is what makes things interesting to me. Labs have been in the education business since the beginning, and it takes many forms.Your lab sales rep can be a gold mine of information for both new and old. From the office perspective, a sales rep can be an interruption and downright inconvenient at times. Most reps are aware that this can be the case and will schedule a time to stop by (they should bring doughnuts). The office should make every effort to make these appointments work. They are great resources for learning about new products and have often driven a hundred miles, eager to share the latest with you. More than that they are a very personal connection to the lab that can make things smoother and more efficient. Take a moment to share, not just grievances, but why something might work better for your office and listen to why things sometimes can’t be done a certain way. This can help develop great partnerships.

Many labs have training programs that range from a few hours to weeks specifically geared to the office personnel. I have been a part of teaching these over the years and can attest that they have great benefits for both the office and the lab. These programs have developed because of frustration at the lack of available training for the office but have become so much more.

New office employees often learn on the job, but that’s difficult. When the new employee can get a crash-course on adjusting or repairs, it moves their usefulness ahead tremendously. If they can come with the old hands at the same time it also bonds them closer and puts them on the same page as the office training continues. Often a tour of the lab is included, and everyone learns what an amazingly complex process it is to produce a unique pair of eyewear for each patient.

We have looked at some of the problems that have occurred between offices and their labs that, in the end, have become learning opportunities. There will always be frustrations, but learning why certain things are important can help make sense of it all. It is often said of any relationship that the most important key to a good one is communication. That is what creates understanding and allows both to grow into a beautiful partnership.

Alex Yoho is an ophthalmic dispensing expert and optical educator.