I’m technically cheating with this entry in “Adventures in Eavesdropping,” since there technically wasn’t any eavesdropping involved, but it’s a continuation of the observations I’ve made in that miniseries.

I recently discovered an absolutely charming little street near where I live in Texas that used to be a residential neighborhood, but whose houses have been converted into small businesses. There are bakeries, cafes, shops, and, for the intents and purposes of this article, an OD’s office. Upon seeing it, I was immediately enraptured: A 1960s-era house converted into a dispensary? I had to see this.

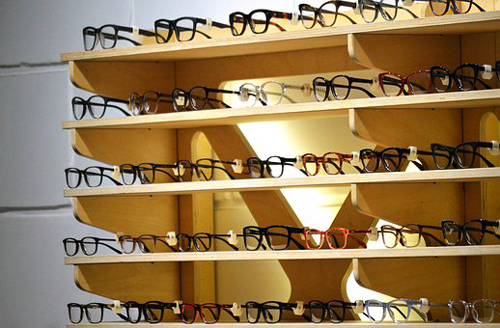

Going inside, my already fevered imagination went into overdrive: This was nothing short of a dream office. Whoever had designed it had been nothing less than an architectural genius. The front hallway had been converted into the reception area, the bedrooms had become exam lanes, and, in a coupe de grace of interior design, the gorgeous sunken living room—complete with what appeared to be original wainscoting—was the dispensary itself, with recessed shelves used to hold display stands for frames. It was venturing down into that dispensary, though, and greeting the optician on duty that day, that I realized why I hadn’t heard about this office in the North Texas opti-sphere, and why it was curiously deserted on a Friday morning in spring when the other doctors’ offices in the area were healthily populated.

Going inside, my already fevered imagination went into overdrive: This was nothing short of a dream office. Whoever had designed it had been nothing less than an architectural genius. The front hallway had been converted into the reception area, the bedrooms had become exam lanes, and, in a coupe de grace of interior design, the gorgeous sunken living room—complete with what appeared to be original wainscoting—was the dispensary itself, with recessed shelves used to hold display stands for frames. It was venturing down into that dispensary, though, and greeting the optician on duty that day, that I realized why I hadn’t heard about this office in the North Texas opti-sphere, and why it was curiously deserted on a Friday morning in spring when the other doctors’ offices in the area were healthily populated.To be quite blunt, the frame selection was awful.

That became quickly apparent when one of the first things out of the optician’s mouth was an apology for not really stocking men’s frames. After she said this, I took a quick glance at the frames behind her and realized, sure enough, of the five recessed shelving units used to hold frames, one had men’s frames, the other four women’s. A turnstile in the corner of the living area held their selection of kids’ frames. With each shelving unit holding four frame poles, each with fourteen slots, that means the office had 280 adult frames, and out of those, only 56 were men’s. Of those 56, the majority were either aviators or very generic looking wire rims. I was helpfully informed that they also offered a selection of dead-stock men’s Luxottica frames, which were in a strangely placed shadowbox that could only be accessed by standing on the staircase leading down into the dispensary/living room—I suspect this had once been an awards display case the owners co-opted after buying the house. For a moment I wondered if this were indeed some sort of boutique optical nominally geared towards women, but a second glance at the office business cards—with “Family” in the business name—informed me this was an office meant to cater to everyone.

I took a further look around, thanked the optician for her time and left. The thing about my visit is that, while I had gone in partially to scope the place out, I really am looking for a new pair of frames right now, and might have made a purchase had they offered a wider selection. The office is in an excellent location, has a design and “angle” that would go over very well with the local population, and a layout that provides a unique and literally homey experience. Were they to market themselves as an exclusively female-oriented boutique, I can see them doing a lot better and establishing a positive reputation in the local opti-world. Similarly, they could diversify their selection and stick to the “family” name. There’s just a major disconnect between how they present themselves and the frames they offer. It’s an object lesson in how frame selection and marketing can make or break a practice.