PROBLEM SOLVING 101:

HOW TO TROUBLESHOOT LIKE A PRO

By Johnna Dukes, ABOC

Release Date: November 1, 2019

Expiration Date: February 5, 2022

Learning Objectives:

Upon completion of this program, the participant should be able to:

- Learn the steps for troubleshooting complaints.

- Learn the steps to remedy a complaint.

- Learn the importance of having a system and checklist for troubleshooting.

Faculty/Editorial Board:

Johnna Dukes, ABOC, is a board certified optician since 2001. She is a member of the FNAO and sits on the Board of Directors at OAA. She is the owner of an optical boutique Optique, She has experience in both private practice sector as well as the retail chain setting. She has a wide range of experience varying from optical support staff to optical management. She is a past president of the Opticians Association of Iowa. Johnna is an ABO approved speaker.

Johnna Dukes, ABOC, is a board certified optician since 2001. She is a member of the FNAO and sits on the Board of Directors at OAA. She is the owner of an optical boutique Optique, She has experience in both private practice sector as well as the retail chain setting. She has a wide range of experience varying from optical support staff to optical management. She is a past president of the Opticians Association of Iowa. Johnna is an ABO approved speaker.

Credit Statement:

This course is approved for one (1) hour of CE credit by the American Board of Opticianry (ABO). ABO Technical Level 2 Course STWJHI001-2

Picture yourself dispensing glasses for a new patient (let's call her Jane) who is putting on her newly purchased glasses, the ones you helped her select. Jane immediately takes the glasses off and says she can't wear them; the glasses make her feel dizzy. What do you do? Do you panic? Do you blindly offer to remake the glasses? Do you set Jane up with a recheck with the doctor? Do you think Jane can tell that you are freaked out? Do you wish there was a better option? Guess what, there is! I'm going to help you create a system so when you're presented with this situation, you don't have to resort to panic; you can rely on your systematic approach to troubleshoot and solve the problem. Better than that is the fact that sometimes a patient having a problem with their glasses isn't a problem at all, it is an opportunity to "wow" them with your professionalism and gain their confidence. If you're ready to learn the skills of the optical superhero, then read on my friend.

Picture yourself dispensing glasses for a new patient (let's call her Jane) who is putting on her newly purchased glasses, the ones you helped her select. Jane immediately takes the glasses off and says she can't wear them; the glasses make her feel dizzy. What do you do? Do you panic? Do you blindly offer to remake the glasses? Do you set Jane up with a recheck with the doctor? Do you think Jane can tell that you are freaked out? Do you wish there was a better option? Guess what, there is! I'm going to help you create a system so when you're presented with this situation, you don't have to resort to panic; you can rely on your systematic approach to troubleshoot and solve the problem. Better than that is the fact that sometimes a patient having a problem with their glasses isn't a problem at all, it is an opportunity to "wow" them with your professionalism and gain their confidence. If you're ready to learn the skills of the optical superhero, then read on my friend.

CREATE A SYSTEM ASAP

Having a system communicates to the patient that you are prepared and perfectly able to take care of their needs. You are their optical superhero and have everything under control. It immediately puts the patient at ease which in turn, makes you more comfortable too. As more and more opticians decide that our profession is so much more than "just a job," troubleshooting skills become the key differentiator between "order takers" and pros. Being skilled at evaluating, analyzing and solving the wearer's eyewear problems saves on valuable chair time with the doctor and demonstrates your value both to the patient and to the practice. By the way, do you think that online retailers can troubleshoot fitting problems for the eyewear they sell? No, they cannot! Troubleshooting needs to be a hands on, in-person professional consultation, e.g., you, a professional optician with a system!

Let's review the essential skills you'll need to troubleshooting like a pro: Listen, ask the right questions, take charge, poise in the face of a challenging situation and effective followup. Still with me? Let's jump in.

INFO GATHERING

Your first steps are going to include a LOT of information gathering. Here is where we are going to have to be good at asking the right questions and effectively listening. What we're looking for here is a "Chief Complaint"—what is it exactly they are struggling with?

Your first steps are going to include a LOT of information gathering. Here is where we are going to have to be good at asking the right questions and effectively listening. What we're looking for here is a "Chief Complaint"—what is it exactly they are struggling with?

Listen to the patient and then paraphrase, and repeat back to them what you just heard, make certain you understand what their chief complaint is. Next, we need to know how long this has been happening or the onset of the complaint. Easy enough, right? What and when, and make sure you're writing this all down. Personally, I work with a form that includes the date of their last exam as well as the date the glasses were dispensed. You will want all of the information in one place, so go ahead and ask all of the questions, be thorough and prepare to wow your patient with your troubleshooting expertise.

TURN YOUR INFO INTO ACTION

Armed with this information and having identified the chief complaint, it's time for action. So first, find the Rx. No, I'm not talking about what you ordered, I'd like you to find the actual doctor's written Rx. It is not uncommon in the order entry phase to enter a digit wrong and then to use the order information to check the glasses rather than checking against the actual Rx. So, first things first, get the actual doctor's Rx and cross-check that this is actually what was entered in the order. Sounds simple, but hey, we're all human, and mistakes happen. If the order was entered correctly, then it's time to verify that the lenses received are what was ordered.

NEXT STEPS: MAKE YOUR MARK(S) AND VERIFY

Now, let's take a look at the glasses in question, which are progressives.

Now, let's take a look at the glasses in question, which are progressives.

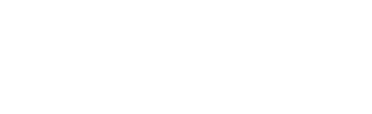

Step 1. Start by recreating the ink marks on the glasses (Fig. 2), find the engravings and using your magic marker, dot the centers of these engravings. PAL engravings are located 17 mm on either side of the major reference point aka prism reference point (MRP/ PRP), more on this later. I like to use lens verification masks for a specific PAL design, which I line up with the engraved reference marks. Another option is to use the correct manufacturer centration to lay out and recreate reference marks (Fig. 1). (Every PAL design has a unique centration chart, and the drop varies among PAL designs.) Whether you use the lens mask or the centration chart, when all reference marks are visible you are ready to verify. Now that we've got the glasses marked up, let's double-check to see if what you ordered is indeed what you received.

Step 2. Verify the distance power in the lensmeter using the distance reference circle.

Step 3. Verify the add power under the temporal side engraving.

Step 4. Verify that the fitting height is as ordered.

Step 5. Verify that the monocular PDs (measured from the bridge center to the fitting cross) match the monocular PDs ordered. If binocular PDs were ordered, then measure the distance between the right and left lens MRP/PRP markings.

Step 6. Having verified that lenses have the prescribed power and the centration and fitting heights as ordered, it's now time to see if the fitting cross aligns with the patient's pupillary center horizontally and vertically. Ask the patient to put the frames on. You want them to position the frame as they wear it. Before they put the frame on, always explain that the lenses are marked so that you can check for proper alignment. Otherwise, they become disconcerted when they put on lenses that have markings on them. Now verify that the fitting cross aligns with the patient's pupil center horizontally (PD) and vertically (fitting height). (Fig. 2) Note: When verifying height for a lined bifocal, the segment line should align with the lower lid margin, and when checking the height for a trifocal, the top segment line should align with the lower pupil margin.

If everything lines up, it's on to the next step. If not, then you may have uncovered the problem. Fitting height issues can sometimes be solved by adjusting the frame to get the fitting cross height to align with the patient's pupil center and line of sight. Other times a re-order of the lenses is required. First, try to adjust the fitting height by raising or lowering the placement of the fitting cross by adjusting the nosepads. Increasing pantoscopic tilt can have the effect of lowering the fitting cross when too high in an acetate frame, and it will make the reading area more accessible. Less panto will have the effect of raising the fitting cross in an acetate frame. If this solves the problem, then we've won the battle. If not, you may need to reorder lenses with correct heights. (Note: Make sure that the frame is adjusted to the patient before taking height measurements so that the centration of the lenses in the frame match the final "as worn" position of the frame on their face.)

If we haven't solved the problem, then we're on to the next step. Check the PD in the glasses they were previously wearing. Yes, patients can adapt to prism induced by centration errors, and when we place the correctly centered lenses in front of their eye, it will feel off. What to do? Do we order the lenses with the prism that the patient has become accustomed to? Do we tell them that there is an adaptation period to get used to the correct lenses? Most suggest that you reach a compromise and ease the patient back to the correct centration. Don't correct all at once, split the difference between the correct centration and the centration/ prism they've become accustomed to, and on the next pair take them back to the correct centration with zero prisms.

How does this frame fit relative to how the pair they were previously wearing? Are the glasses sitting squarely on the face or is one side higher than the other? And let's take a peek at face form, vertex distance and pantoscopic tilt. Is there too much or too little of any of these? For example, a patient who is used to wearing a good bit of face form and then goes to a flatter fitting frame will often report that they are unable to use their peripheral vision or that they feel they see the edge of the frame. Remember the peripheral vision in lenses is optically inferior due to inherent marginal astigmatism, and adding a bit of face form can move the edge of the lens out of the line of sight.

DID YOU CHECK THE PRP?

As promised, let's discuss the PRP, or Prism Reference Point. We are taught that this reference point on a PAL lens is the optical center and referred to as the Major Reference Point or MRP, unless there is prescribed prism, then this reference point is the Prism Reference Point and is used to verify prism. (Note: Prism thinning used by PAL manufacturers is treated as a prescribed prism.) This is the part of verifying a progressive lens that is often overlooked and although rare, I have personally encountered discrepancies in the amount of yoked prism between right and left lenses. Yoked prism used to thin PAL lenses should always be equal between lenses. When you lay out your lens on the manufacturer's centration chart for mark up, locate/mark the dot beneath the distance reference circle. This is the area used to verify the amount of prism present in a progressive lens. If prism is present, is it equal to that of the other lens? If any prism is present, does it fall within acceptable limits when it comes to the law of canceling and compounding prism? Remember, prism cancels when the amount of prism in both left and right lenses is equal and with the same base direction; if both have base up prism (Up and Up) or both bases are down (Down and Down) or one lens has base in and the other base out (In and Out or Out and In).

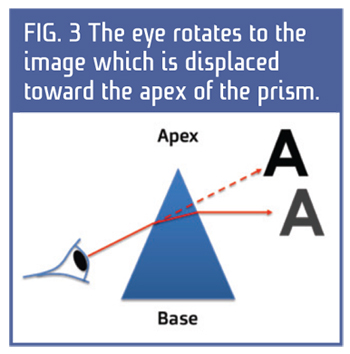

Conversely, the prism is compounded when one lens has a base up prism, and the other has a base down prism, or if both have bases in, or both have bases out. (In and In, and Out and Out.) Think of what happens to the eyes which rotate toward the apex of the prism (Fig. 3). Bases out in both lenses cause the eyes to converge in. Base in prism in both lenses causes the eyes to diverge out toward the prism apexes. One lens with base up and the other down is forcing one eye to rotate down and the other up. Is it possible the amount of prism is unequal from lens to lens?

Conversely, the prism is compounded when one lens has a base up prism, and the other has a base down prism, or if both have bases in, or both have bases out. (In and In, and Out and Out.) Think of what happens to the eyes which rotate toward the apex of the prism (Fig. 3). Bases out in both lenses cause the eyes to converge in. Base in prism in both lenses causes the eyes to diverge out toward the prism apexes. One lens with base up and the other down is forcing one eye to rotate down and the other up. Is it possible the amount of prism is unequal from lens to lens?

This can be the case when yoked base-down prism is used to thin PALs but unequal amounts are used between the right and left lenses, or if one lens is re-made.

I can tell you from personal experience that I learned this lesson as a young optician. When I experienced uneven prism thinning for the first time, I didn't know what was wrong with the lenses, and I remade them several times before it dawned on me to check the prior pair for prism thinning, and there it was. The patient was wearing a pair of glasses for the prior three years that had unequal prism thinning between right and left lenses. Therefore she was wearing a prism to which she had become accustomed. This is a lesson I will never forget as I remade the lenses four times for the same patient— yes, you read that right, four times. Needless to say, when troubleshooting now, I NEVER overlook checking the PRP of both lenses to assure equal prism thinning.

FIT MATTERS

In a patient who has a change of vertex distance, their complaint will vary depending on if the patient is a myope or a hyperope. A minus lens moved closer to the eye becomes more minus and feels stronger to the wearer but if moved farther away, becomes more plus and feels weaker. Conversely, a plus lens moved closer to the eye becomes less plus and feels weaker, and if moved farther away becomes more plus and feels stronger. (It is important to note that this lens will still read the same power in the lensometer, these changes in perceived power are due to vertex distance differences between the refracted value and the actual as worn value. This can be an issue if the patient has a significant prescription, and the refracted distance and the frame fit vertex distance vary substantially.

Remember that when the patient is in the exam chair being refracted, the phoroptor sits approximately 14 mm from the patient's eye, and your frame selection will likely change this measurement. (i.e., If the patient has chosen a frame with no nosepads, this lens will now fit at about 10 mm vertex— this is 4 mm different from how they were refracted.) In higher prescriptions, this becomes an issue, and we may need to provide the lab with a compensated power that reflects the power increase or decrease due to the vertex distance difference. This should be done before ordering lenses. If you've identified the problem at this late stage during troubleshooting, then your only options are to adjust the frame to fit closer or further away. If adjustments to the frame don't correct the problem, then you will need to run the vertex compensation formula and reorder the lenses.

Here's an example of the vertex compensation formula. Using the data from above, power is D2/1000 for every millimeter of change to the vertex. For example, a -8.00 lens is fit 4 mm closer (fit at 10 mm refracted at 14 mm). How does this affect the Rx? Use the power (-8.00) and square it (64), then divide it by 1,000 (0.064.). Then take this times the 4 mm of vertex change (0.256.) Remember that we're using a minus lens, and we're sitting it closer to the eye, therefore inducing more minus, so this lens that we ordered at -8.00 truly is perceived by the patient at -8.25 to compensate for vertex we should have ordered at -7.75.

Did you look at how the frame fits overall? Are they sitting squarely, or are they crooked? Is the pantoscopic tilt even between the two lenses, or are the lenses crisscrossed with the adjustment being uneven at the bridge? Is the face form even, or is one lens closer to the eye than the other? Sometimes it is best to take the frame back to 4 point alignment and start the adjustment process over from square one.

LOOKING BACK TO MOVE FORWARD

Did you look at the fit of the old glasses? Is there a big difference in how the old ones and the new ones fit? Often personal preference will dictate how a patient will want to have their glasses fit, but sometimes prescriptive change will affect the way a new prescription will need to fit to work properly. Evaluating this prior to making the new glasses is a good practice to get into, as doing this after the completion of the new Rx can require a remaking of a lens. For example, I have a patient who likes to wear their glasses lower on the nose than I would like for them to sit. However, that is what she wants, so if I were to have taken the progressive lenses' measurements based on fitting them as I want them to fit, I'd have to remake the lenses set higher after fitting them to sit lower on her nose as she'd prefer to wear them. Again, these are best practices to do in the process of lens and frame selection, but if you're at this point now, this step was likely missed earlier in the process.

Check the prior Rx. Was there a large change from last time to this time? Does the problem fit this scenario? There are any number of issues that can cause large changes in prescription, and if you didn't notice that there had been a change at the time of order, this might be the time to have a conversation with the patient about what to expect during the adaptation phase of new glasses. Of course, every patient experiences differences in Rx differently; however, the key is giving the patient the proper instructions on what to expect during that time period. If you say nothing about the Rx change at the time of order, you make the dispense harder as the patient will assume that the glasses are wrong as they are different from what they had been experiencing. In my experience, it is best to head this off at the pass and have this conversation before they order glasses rather than after you've dispensed them, but if we're talking about this now, it could be that this step was missed earlier.

Also, in looking back at the previous pair of glasses, it's a good idea to check to see if there has been a change in the lens material. Differences in chromatic aberration are very real and are perceptible to many people. This is often something patients can react adversely to, I've seen patients who can't adapt to polycarbonate after wearing plastic or Trivex, and I've also seen patients who can't adapt to ultra-high-index lenses after wearing lower index products.

Evaluating if there has been a change to the material will be helpful information for you to gather.

Next, let's take a look at the previous lens design. If the patient is a single vision, was their previous lens aspheric and did you duplicate this design? Or if the patient wears a PAL, was their previous lens a short corridor or standard corridor design? Do you understand the difference or when to use one over another? It's also important to check the previous amount of prism thinning, even if the amount is even from lens to lens; an older pair might have used a different amount, and this can be perceived by the patient even though the law of canceling prism dictates that the result should be no prism, sometimes the patient can perceive the different amount. (For example, yolked prism is often used in vision therapy or for people who've experienced neurological trauma or stroke.) Understanding what is in the pair of glasses your patient is currently wearing will tell you a lot about what the current issues might be.

DECODING COMMON COMPLAINTS

While troubleshooting, it is usually best to work through your checklist, but as you begin to get really proficient in solving problems, it is likely you will be able to zero in on what the problem is just by understanding what the patient is experiencing based only on their complaint. Remember, patients don't "speak optical," it is difficult for them to tell us their PD is off because they don't really understand what that means, but they do know something doesn't feel right to them. Here are a few things they might say and what they really mean.

For example, if a patient reports feeling like the room is spinning around them, or if they report feeling drunk, often this patient is feeling the effects of "swim." Often this patient is a new progressive lens wearer or someone who is a primary contact lens wearer who is trying spectacles after not having worn them for some time. What is likely happening is that they are utilizing the peripheral zones of the lens rather than looking out of the center. Also, in the case of the first time PAL wearer, the brain is noticing motion changes when they move their head. As the eye moves through the corridor, they will notice the power change from distance to near. As this patient continues to wear the lenses, the brain will adapt to these feelings of motion and will likely negate the feeling of motion as it is a constant, and the brain tends to negate things it sees constantly. (Interestingly, did you know that you actually see your nose all day every day, but your brain has chosen to negate it from view?)

A patient reports feeling "like I'm inside of a bowl like I'm really short, and everything around me is tall," or "like I'm walking up a hill." This patient is likely experiencing base down prism. Remember the rules of prism light deviates toward the base, and the image is displaced toward the apex. If the image appears higher, the base direction is down. So in this case, we need to mark up the lens to see which part of the lens the patient is using versus where the actual center is located. We need to evaluate the portion of the lens the patient is looking through to determine if prism exists there. The reverse of this situation will also be true if the patient reports feeling "like I'm walking downhill," this patient is experiencing base up prism.

If a patient reports seeing "rainbows when it is bright outside," this patient may be experiencing internal lens reflections due to an exposed polished lens edge, or this could be chromatic aberrations caused by low Abbe lens materials. If the patient is in a low Abbe value lens material, make sure that the lens is fitting as close to the eye as possible and add face form. Chromatic aberration does not affect the central portion of the lens, only the periphery.

If a progressive lens patient says, "I can't read in my lenses," this is likely that they either aren't reaching the full add power in the lens. Mark the lenses and confirm the proper fit. Add a bit of pantoscopic tilt for easier access to the reading area. Make a note in their file for future PAL orders to use a short corridor design.

There's also the ever popular "I can't see ANYTHING at all in my new glasses." If you have taken all the steps to see if everything else checks out, this patient may be one who has experienced buyers' remorse and wants a refund. Know the practice policy for non-adapts.

Having a plan for troubleshooting is such an integral part of becoming the optical superhero you were destined to be. Never fear, your troubleshooting checklist will be your guide. If you take the proper steps, ask the right questions and turn that information into solutions for your patient, you will be the optical superhero your patient needs!