By Palmer R. Cook, OD

Yogi Berra said, “The future ain’t what it used to be,” and that’s certainly true for today’s elderly citizens. They are healthier, more active and more likely to interact with others and with their environment. Elderly is often defined as beginning at age 65, and even that may change.

The U.S. Department of Commerce has estimated that there will be an increase in the percent of our population ages 65 and older from 15 percent in 2014 to 24 percent in 2030, just a decade from today. Our aging population is growing, and older adults are staying in the workforce longer. They are also more active in sports including tennis, handball and other sports requiring good visual acuity, stereopsis and stamina.

Although statistics show the increasing percentage of seniors in our population, that’s not the whole story. Aging patients have needs that are more complex and time-consuming than younger patients. The tools and technologies that are needed for aging patients are often more expensive to acquire, use and maintain.

Even if problems related to pathologies affecting vision are excluded, there are special considerations that relate to meeting the needs of elderly patients. Their mobility may be affected. Falls and broken bones become more problematic. Hearing loss is a factor, and impairment of cognitive function may interfere with every aspect of their daily life. They may have a strong desire to conceal changes in their vision from friends and family. Are you and your office equipped and ready to meet the special needs and challenges of this increasing need for care for the elderly?

PHYSIOLOGICAL CHANGES AND SENIORS

Refractive changes related to aging occur throughout life. The minimal amount of light needed for visual tasks doubles about every decade. Thirty-year-old mothers fuss at children with the admonition, “You will ruin your eyes reading in light like that,” because her eyes need about four times as much light to see in reduced illumination.

Glare recovery time is extended, causing an elderly person who is exposed to excessive light to take longer for his or her vision to adjust. This is one of the reasons that people over 65 tend to have more difficulty driving after dark. Other changes include smaller pupils reducing the amount of light reaching the retina. This is especially troublesome during mesopic (e.g., twilight) driving situations.

Facial anatomy changes with time. Glasses are supported by the nose, and cartilage loss in the nose can make the bone structures in that area more prominent. The outer layer of the skin (epidermis) thins, and the skin sags as the result of collagen loss. Moles and other skin anomalies become more prevalent, and the skin covering the outer ears becomes thinner.

Mobility is affected by cardiovascular and muscular problems, and arthritic changes in the joints may reduce the range of movement. Restriction of head turning (right or left) is especially troubling for drivers. Wide angle rearview mirrors may be needed to help seniors deal with “blind spots” that conceal cars approaching from behind on either side.

ACCESS, MOBILITY AND SAFETY

Is a ramp available for easy entrance to your office? Are the patients’ chairs tip-resistant, sturdy and equipped with arms to make arising easier? Do you have at least one restroom with a five-foot turning radius for wheel chairs? Is your staff CPR trained? Elderly patients are subject to falls, so staff should be trained on correctly handling that kind of situation. Your first aid kit should be available, well stocked and regularly checked for needed re-stocking.

Does your patient have a mobility challenge such as a need for a walker or wheelchair? If so, folding wheelchairs are available for less than $200 that can be used for transport from the car to the exam room or dispensary. They are easily stored when not needed. One caution: The caregiver or patient may appreciate not having to load a chair for the patient, but it should be made clear that the staff cannot be responsible for assisting the patient into or out of either the car or the office’s wheelchair.

If the patient uses a walker, having a transport wheelchair available may make the office visit easier and more efficient. Whether you have a transport wheelchair or not, a wheelchair glide allows your patient to remain in the wheelchair for testing as well as for attention in the eyewear design and fitting areas (Fig. 1).

SCHEDULING

Schedule elderly patients for your office’s “quiet times” when you and your staff can take the extra time that elderly patients so often need. Whether the elderly person calls personally or whether a caregiver calls, triage as best you can over the phone. Asking about eyecare insurance goes without saying these days. As you collect information over the phone, remind the patient to bring a list of all medications (with dosages) as well as present and even previous eyewear, their insurance card and ID. Inquire about mobility issues. A list of eye and vision-related concerns can be helpful. The patient or their caregiver may know when the patient “does best,” and you should schedule accordingly. Some elderly patients are most alert in the mornings, and by late afternoon they fade or vice versa.

A text or email reminder a day before any appointment is a good practice, but only if the patient or caregiver who has scheduled time with you communicates in that fashion. Often a phone call is best for aging patients. Caregivers will know if the person they are assisting is having a “good” and “not-so-good day.” They should be told that if the appointed day turns out to be not so good, rescheduling is recommended. Whether your office provides full primary care, or if you are an eyewear-services-only practice, scheduling elderly patients appropriately can be an appreciated service for all concerned.

EXAMINATION

Elderly patients with strong lens powers sometimes have difficulty maintaining a fixed distance or position behind a refractor. Patients may discover that moving away from the refractor or head tilting while the cylinder axis is being determined or subjective phorias are measured “helps.” Because of this, a trial lens refraction or an over-refraction may be needed.

For over-refractions and subjective muscle balance testing behind the refractor, the MRP of strong existing lenses can be marked and a notebook ring reinforcer (7 mm aperture) can be centered and secured with Scotch “misty” tape to help keep the patient positioned for testing. Unless the refractive changes are large, small differences in the refracting vertex distance will not be significant. Rather than calculating the resultant, simply use the previous Rx, trial lenses and your lensmeter to find the new Rx.

If your patient is binocular, Vectographic refraction is efficient and yields a very wearable result. If you use a bi-chrome technique in refracting, direct your elderly patient’s attention to letter quality. Lenticular changes may make the red background brighter, which can be confusing for elderly patients.

It’s human nature to have hopes and expectations. When new lens powers are prescribed for elderly patients, it’s a good practice to allow the patient to compare his or her vision in the existing glasses with the improvement resulting from viewing through the new Rx in trial lenses.

Elderly patients with short-term memory problems may find the time lapse between viewing with present glasses and the trial lenses a challenge. In these cases, three trial lenses can be used for each eye so the change from old to new is immediate. The first two lenses are the change in sphere power and the new cylinder power at the new axis. The third lens would be the old cylinder power with the opposite sign at the old axis (e.g., Existing Rx +2.00 –1.50 x 020, new Rx +1.50 – 0.75 x 040. Trial lenses: – 0.50 DS, – 0.75 x 040, +1.50 x 020). The plus cylinder trial lens neutralizes the cylinder in the existing Rx, just as the minus sphere neutralizes the excess plus sphere power in the existing Rx.

Innumerable diseases affect eyes and vision, and there are many genetic and environmental conditions that adversely affect the visual system. The examining doctor should be well versed in the testing and prescribing techniques for elderly patients, however there are eyewear design issues which should not be overlooked for elderly patients.

SPECTACLE LENS CONSIDERATIONS

Blocking UV may be particularly helpful for elderly patients who have not had cataract surgery because as fibers of the crystalline lens age they also tend to exhibit fluorescence when exposed to UV.

Internal spectacle lens reflections are also detrimental to retinal images. There are three ways to address this problem. In order of decreasing efficacy, they are:

- Using top-quality AR lens products.

- Using a lens material with lowest practical index, and 3. Using a light tint. Fortunately, these three options can be combined for an optimal effect.

Anti-reflective (AR) lenses improve the performance of every lens prescription and every lens material. A top-quality AR with smudge resistance and anti-static properties should be used. AR enhances the ray path for the primary retinal image, and the internally reflected light is dimmed.

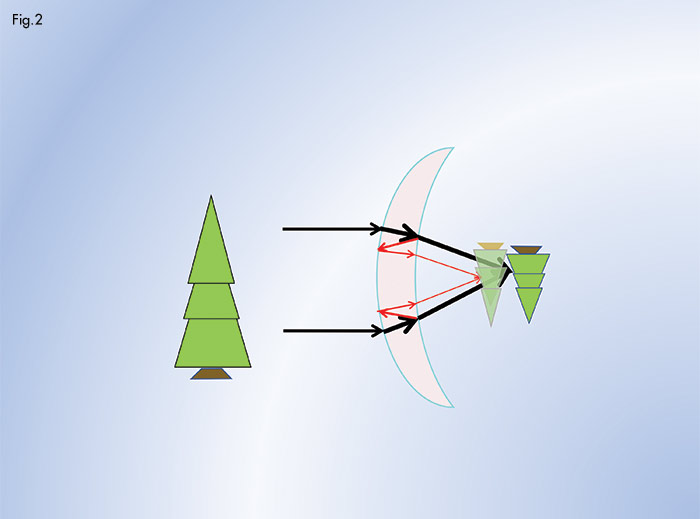

The index of the lens material controls its reflectance. As index increases, reflectivity increases with index according to the formula r = [(n – n’)/(n + n’)]. (r = reflectance, n = Index of air (1.00), n’= The index of the lens material) The most troublesome ray path for reflected light in terms of lens performance is shown in (Fig. 2). The red arrows show the ray paths that create “ghost images” of oncoming headlights when driving and similar ghosting of TV and computer screens when viewed under low ambient lighting. Under photopic lighting (such as daylight or normal room lighting) this same ray path creates a veiling of the primary retinal image. With lower index lens materials, reflectance is less, and ghosting and veiling is proportionately reduced.

Because accommodative convergence is no longer available for elderly patients, BI prism for near only is sometimes needed. Franklin bifocals with prism in the reading areas are available (Arthur E. Brown of Quality Optician, Northampton, Pa., is a source) or your lab may be able to supply modern cement segs with prism.

TINTS

Light tints also reduce the ghosting and veiling effects of internal lens reflection (Fig. 2). For an index of 1.66, a tint alone that reduces transmission from 87.8 percent (the transmission of a non-AR 1.60 lens) to 82 percent reduces the brightness of ghost images and the veiling effect on the primary retinal image by about 31 percent.

Glare recovery time increases with age. Oncoming headlights and other light sources can cause significant problems for elderly drivers, especially when they are challenged by low contrast hazards. This problem is exacerbated by lengthened reaction time, as well as by spectacle lenses and filmed windshield surfaces.

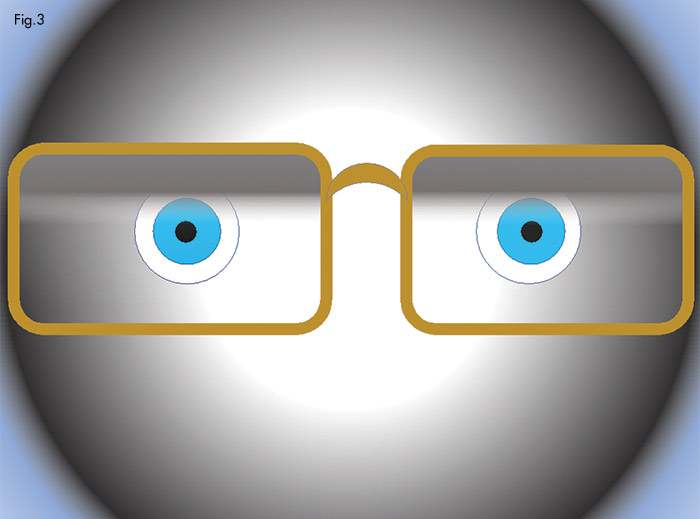

A dark-at-the-top gradient tint which fades to clear when looking straight ahead (Fig. 3) offers a rapid and convenient way to avoid glare recovery problems. This will not circumvent the need for sunglasses for prolonged use, but for short-term exposure such as walking from the house to the mailbox or from the car into the mall on a bright day, it allows the wearer to avoid the problem of slowed glare recovery by simply tipping his chin downward to view through the tinted area when the ambient light is excessive. This type of tinting also shields against useless annoying light from above.

WEIGHT

Weight of the frame and lenses can be an important consideration. Using rounded rather than rectangular lens shapes reduces lens weight. Wider bridges (with adjustable pads) and turnback temples can give the needed overall eyewear width and allows you to use a smaller lens size. Trivex lens material has the lowest density (1.11) of all ophthalmic lens materials. The impact resistance of Trivex is equivalent to that of poly, and it has a somewhat lower index (1.54 vs. 1.586) giving it lower internal lens reflectance. From about –12.00 to +10.00 Trivex will be lighter than poly, although the difference in weight is not as much at the extreme limits of this range.

FRAME CONSIDERATIONS

As patients age their priorities tend to change. An elderly patient who may have valued acuity and appearance over comfort a few years earlier may find a small increase in acuity or a more stylish frame unimportant if the eyewear is uncomfortable. Because of this, it is important to evaluate obstacles to a comfortable fit as frame selection begins.

Shortened vertex distances effectively enlarge the distance and near sweet spots of PAL lenses, and this also widens the corridors. Wide temples that block peripheral vision can be especially hazardous for the elderly and should be avoided. Elderly patients often experience dry eye problems. Using a wrap frame or even moisture chamber frames can offer some relief.

DISPENSING

Allow extra time for dispensing. Explanation of adaptation, eyewear care and the importance of follow-up care is important and may require more explanation. It is discouraging when confused elderly patients return complaining about recently dispensed eyewear, only to find they are still wearing their old glasses. Such things occur because the patient decides to try the old eyewear and becomes confused, perhaps because the old eyewear feels “familiar.” Looping half-inch Scotch tape around the bridge and folded temples of the old glasses after a “tuning up” for use as spares helps avoid such situations.

Elderly patients often have cliques or small groups of friends of similar age who socialize regularly. In some cases, members of these groups watch each other for signs of “slippage.” Because of this you may find stout resistance to replacing an ancient dilapidated frame.

The weight of the glasses is mainly supported by the nose. Thinning skin, a long history of pads making permanent indentations and moles or other skin anomalies all tend to be problems for elderly patients. Using oversize pads can spread the supported weight over a larger area. However, larger pads can have an insulating effect that raises the temperature of the skin upon which the pads rest and can encourage yeast, bacteria or an allergy problem to arise. Other approaches include using silicone or PVC saddle strap nosepads (available from Tabco Products) that transfer some of the weight to the bridge of the nose or attaching a Unifit bridge from Hilco Vision to the frame. (Watch the video on Hilco’s YouTube channel to see how it’s done.) Pads can be attached directly to zyl frames using either adhesive or screws to shift the bearing area on a challenging nose. Adjustable pad arms can convert a zyl bridge for a better fit.

The bearing area of any frame should be on the upper third of the sides of the nose. To locate this area, press the tips of your index fingers as high on the side of your nose as possible. Then slowly inhale as you slide your fingers downward. You will easily be able to locate the point below which pressure will impede breathing. Elderly patients may be highly sensitive to anything that restricts breathing. They may have moles, skin problems or indentations from years of wearing nosepads, all of which may need to be avoided.

If adhesive pads on zyl frames or adjustable pads cannot be placed high enough, one solution is to use adjustable pads with the pad attachments moved higher on the eyewire. Attaching an auxillary bridge may be an option.

PTOSIS AND ENTROPION CRUTCHES

Ptosis crutches (Fig. 5) can be used for both blepharochalasis and ptosis if surgery is not an option. Entropion (a turning inward of the lower lid) is more common with the elderly. It causes pain because the lashes abrade the cornea. An entropion crutch (Fig. 6) is a small metal wire with a nosepad attached horizontally. Entropion crutches are usually attached to the lower nasal part of the eyewire. They extend to about the center of the lower lid and gently press through the skin on the outward turned edge of the tarsal plate. This flips the lid into its normal position against the globe and gives immediate relief from the corneal abrading. Both types of crutches are available custom made from Arthur E. Brown of Quality Optician, Northampton, Pa.

CLEANING EYEWEAR

Eyewear requires care, and elderly patients are often prone to lens smudging. They may not even realize that filmed or smudged lenses are interfering with vision.

First, carefully flush the eyewear with mild warm water to remove grit. Using hot water can cause thermal shock and subsequent crazing to AR lenses as well as causing screws to loosen. Second, use the recommended lens cleaner and a grit-free cloth or tissue to gently wipe the lenses and frame. Caregivers and patients should be given these instructions verbally and in written form.

A once-a-week overnight soaking by immersing the eyewear in a weak solution of mild dishwashing detergent and water in a tumbler will help eliminate oils that build up in eyewire and cord grooves. This reduces smudging and makes cleaning easier. (Dishwashing detergents that claim they are mild or easy on the skin have a low pH and tend to be eyewear friendly because their pH tends to be lower.)

DRIVING

Driving is very much a vision related task. The elderly are challenged by slowed reaction times when they operate a motor vehicle. For night driving, the nominal (i.e., across the visible spectrum) lens transmission should be no less than about 82 percent. Elderly drivers need more light, and when available light is limited trouble may arise before the driver can identify a hazard. A 20 percent tint effectively reduces the reach of the headlight by that same amount, and the reach of the headlights is further reduced if the windshield is tinted as well as the spectacle lenses.

Today’s headlights are no longer sealed beam pit-resistant glass. Headlight lenses should be clean and in good condition. Elderly patients who drive at night should be advised to check their headlights and have the lenses renewed by polishing or replacement if they are pitted, scratched or fogged.

In cold weather, air inside automobiles tends to be quite dry. Car humidifiers are available and may give relief from dry eye problems especially for extended trips. Increasing the amount of recirculated air in cold weather also helps keep the humidity up inside the car. Car vents should be adjusted so that air flow over the eyes will not increase evaporation of the tear film.

Older eyes generally require additional light. Because of this, anti-reflective lenses are particularly important for mesopic (twilight) driving, as well as for night driving. Twilight driving may be especially difficult for elderly drivers because of reduced contrast sensitivity. Film on the inside of the windshield can be a significant and often overlooked source of light scatter. This can be reduced significantly by a weekly cleaning of the inside of the windshield.

During daylight driving, light reflected from the top of the dashboard is reflected into drivers’ eyes from both of the windshield’s surfaces (Fig. 7). This light creates a veiling of the retinal image which is greatly reduced by using polarizing lenses. Because elderly drivers have longer reaction times, the more advance warning they have of an impending accident, the better chances are that they will successfully respond.

Often, but not always, elderly patients are special-needs patients. Never speak in an extra loud voice unless you are sure all that volume is needed. It is impolite, and it implies that you are being inappropriately judgmental. Elderly patients belong to the generations that served the younger generations and their country well. They deserve your respect and the best possible care you can provide for them during their twilight years.■

COMMUNICATING WITH OLDER PATIENTS

Here are some tips that will help you and your staff communicate effectively

with older patients:

- Communication can be complicated by a shortened attention span, so use short direct sentences if possible.

- Turn down the office background music system.

- Avoid interruptions.

- Don’t speak rapidly.

- Allow time for the patient to answer your questions.

- A gentle non-aggressive touch on the shoulder as you lean closer to direct the patient’s attention will help keep elderly patients focused on the eye chart or a frame choice.

- Hearing loss is common among the elderly so if you are closer as you speak, you will not need quite so much volume to be heard.

—PC

Contributing editor Palmer R. Cook, OD, is an optometric educator and optical dispensing expert.