US Pharm.

2007;32(4):HS29-HS39.

Complex

regional pain syndrome (CRPS) is one of the most perplexing and debilitating

disorders facing health care professionals involved with pain management. The

exact incidence is unknown, and the lack of precise diagnostic criteria has

hampered efforts to improve research involving therapeutic interventions.

The disorder was originally

reported in the medical literature after the Civil War and was described as a

syndrome of pain, autonomic disturbances, involuntary movements, and changes

in the skin or hair in an extremity with a nerve injury. This constellation of

symptoms was originally named causalgia. Early descriptions of the

pathophysiology of the disorder in the 1940s emphasized the involvement of an

overactive sympathetic nervous system–leading to the diagnosis of reflex

sympathetic dystrophy. Other names used for this disorder include

algodystrophy, shoulder–hand syndrome, posttraumatic

dystrophy, and Sudeck's atrophy.1

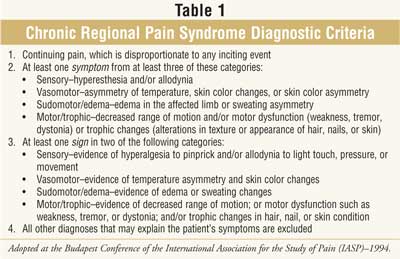

Diagnosis

The identification

of the syndrome remains problematic. Current consensus guidelines have

established diagnostic criteria (Table 1). Pain and hyperesthesia, an

increased sensitivity or awareness of pain, are present in almost all patients

with CRPS. Pain is usually described by these patients as neuropathic in

nature and having the characteristics of burning, pricking, or shooting. Most

patients describe the location of the pain as deep within the affected limb.

2,3 Up to one half of patients will experience deficits in temperature

and tactile perception on examination.2

Autonomic symptoms may include

swelling or edema, skin color changes, abnormal sweating, or alterations in

skin temperature. More than half of patients experience edema in the affected

limb, and the skin temperature difference between limbs is often greater than

1°C. Early in the course of the syndrome, patients are likely to report edema

and a warm extremity. As the disease progresses, edema usually regresses and

the patient will often report a cooler extremity. Skin may appear to be paler,

or even discolored to a blue or purple undertone.2

Motor symptoms vary widely

among patients. In one study, more than 75% of the patients reported weakness

in the affected limb, and 50% reported tremor.3 Patients are also

found to have decreased range of motion and may eventually experience

contractures after disuse of the affected limb.2 In severe cases,

patients may even lose perception of limb positioning to the point of ignoring

the impacted limb. This particular symptom is known as limb neglect.4

Patients often notice decreased hair and nail growth as well as thinning of

the skin with time.2

Incidence and Risk Factors

Very little is known about the

incidence of the disorder. In fact, up to 10% of patients will not be able to

identify an event or injury that precipitated their symptoms.5

Although the disorder has been reported in children, the usual age of onset is

between 36 and 46 years. The majority of cases occur in women. The most common

inciting events include surgery, fracture, casting or immobilization, sprain,

crush injury, and stroke with motor involvement.2

The majority of patients with

CRPS are not able to continue with regular employment, and many of them

require significant assistance with normal household responsibilities such as

cooking, cleaning, and laundry.6

Pathophysiology

In most cases, an

inciting event such as trauma or immobilization leads to the release of

proinflammatory neurotransmitters such as substance P and prostaglandins. This

normal response to pain transmits the stimuli to the spinal cord to initiate a

pain response. As with many injuries, these mediators start the initial warmth

and swelling or edema at the site.3 Up until this point, the pain

response is characterized as a normal physiologic one.

The mystery of this disorder

centers on the perpetuation of this response into a vicious cycle of pain and

disuse of the affected limb. Two theories are proposed in the medical

literature for CRPS. The first is that the mechanism causing the release of

the inflammatory mediators does not terminate appropriately. The second theory

proposes that the clearance of the inflammation mediators is altered and that

they exist in the periphery for prolonged periods. In either case, an excess

of these substances sensitizes the nervous system, both peripherally and

centrally, to the perception of pain. This perpetual painful stimulation is

thought to increase sympathetic tone in the area in response to increased

levels of epinephrine and other constricting catecholamines. Eventually, this

increase in sympathetic drive leads to vasoconstriction, cooling of the

extremity, and possibly atrophy.3 Patients naturally avoid painful

stimuli through decreased use and guarding of the limb. Disuse further

decreases the clearance of catecholamines and impairs venous drainage of edema

in the area.7 In one study, depression and emotional impairment

related to pain associated with increased levels of catecholamines.8

X-rays of limbs impacted by CRPS often show osteoporotic changes in the bone

even as quickly as four to eight weeks after symptoms appear.9

Psychiatric Comorbidity

A long-running

controversy surrounding CRPS and its treatment involves its association with

psychiatric illness. Patients with CRPS commonly experience depression,

anxiety, and phobias with a prevalence that ranges from 18% to 64%. The

incidence of individual psychiatric disorders within this patient population,

however, does not differ significantly from the chronic pain patient

population.10 The severity of depression in CRPS has been linked to

the severity of associated pain, which may indicate a physiologic or

neurochemical link between the two conditions.8 In an evaluation of

a CRPS population, Lynch and colleagues found no evidence that previous

psychiatric illness predisposed to the development of CRPS.11

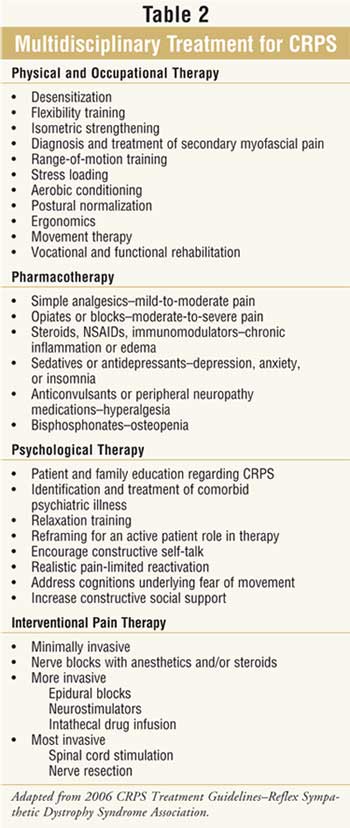

Nonpharmacologic Therapy

Therapy including

physiotherapy, psychological counseling, behavioral therapy, and potentially

neurostimulation are key to success in the management of CRPS (Table 2

). Lack of multidisciplinary care often results in poor outcomes; however,

finding clinicians with knowledge and experience specific to this disorder can

be difficult. Obtaining insurance company reimbursement for these

interventions can also be problematic.8

Physiotherapy is usually directed at

gradual restoration of normal sensory function. This process is accomplished

through occupational and physical therapy. Examples of successful therapy

include progressing from gentle movement of the affected limb to weight

bearing and then on to normal activities. Another example for sensory therapy

may involve initial therapy with textures such as silk and increasing to

rougher textures, and incorporating temperature changes into therapy.12

In one study retrospectively examining 145 cases, those who received physical

therapy reported significantly less pain and a better functional status.13

Successful therapy is most likely to occur with effective pain management

through pharmacologic intervention; see discussion below. Trigger point

injections of anesthetics or pain medications may facilitate therapy with

range of motion exercises. The goal of this rehabilitation should be

normalization of activity or an ergonomically adapted environment to improve

functionality.2

Behavioral therapy is less familiar

to many clinicians, but it is a key part of therapy for these patients. One

example is trained relaxation of muscle groups. This training begins with

unaffected muscle groups and gradually proceeds to the affected limbs. In

controlled evaluations, this practice has demonstrated the benefit of reducing

the spread of symptoms. Another behavioral technique emphasizes the importance

of patient involvement in the treatment process. This procedure, known as

"reframing of symptoms as a call to action," prevents passivity on the part of

the patient. Being actively engaged and involved in treatment is associated

with more positive outcomes.8 Current consensus guidelines for CRPS

recommend that patient's with symptom duration greater than two months should

have a psychological evaluation.2 The combination of psychological

and behavioral therapy may help to break the interaction between physical pain

and stress behaviors, prevent disuse of the extremity, and encourage positive

coping skills as a response to pain.8 The medical literature,

including a meta-analysis, supports this approach for chronic pain patients

but has not been evaluated in CRPS.14

Neurostimulation is a more invasive

technique reserved for more severe cases. Both peripheral and spinal cord

stimulation have been studied for these patients. These interventions are

generally monitored by an interventional pain specialist and considered after

failure of less invasive modalities.2

Pharmacologic Therapy

As with

nonpharmacologic interventions, pharmacologic therapy for CRPS often requires

implementing multiple types of therapy simultaneously. This therapy may

include interventional procedures such as nerve blocks and regional injections

of anesthetics, steroid therapy, therapy for osteoporosis, traditional

neuropathic pain medications, and opiates. At the time of writing, no

pharmacologic therapies were approved by the FDA for treatment of CRPS

specifically. Experimental therapies for treating the disorder, however, are

under evaluation.

Nerve blocks are utilized for CRPS

patients for temporary pain relief and to facilitate compliance with physical

and occupational therapy. These nerve blocks are typically administered in the

medical office setting or as an outpatient surgery procedure by a trained

interventional pain specialist. Although no controlled medical evidence exists

to support their use in specific situations, they are one of the most commonly

employed interventions for these patients. Trials evaluating the use of blocks

often do so in isolation from other therapies. For example, in 2004 a study

conducted by Taskaynatan et al. found no benefit to blocks containing

lidocaine and steroids when compared to placebo. However, this study examined

blocks as an isolated treatment and not in conjunction with other modalities,

such as physical therapy.15 Different types of blocks are

administered depending on the patient's symptoms and the area affected by

CRPS. Sympathetic blocks, intravenous regional blocks, and somatic nerve

blocks are all utilized for symptom management.2 These injections

often include an anesthetic as well as steroids and, in some cases, agents to

block sympathetic outflow.

Systemic therapy with steroids early

in the course of CRPS has shown benefit in randomized trials. In one study

evaluating 30 mg of prednisolone for 12 weeks in comparison to placebo,

patients treated with the steroids experienced less pain over the study

duration.16 A study comparing prednisolone 40 mg to an active

control group, piroxicam 20 mg, in CRPS related to stroke demonstrated

positive outcomes for both pain and quality of life (QOL) for the

steroid-treated patients. The group receiving piroxicam did not show any

significant change in either pain or QOL over the study period.17

Based on the available information, steroids should be considered early in

management of CRPS to improve long-term outcomes.

As discussed earlier, CRPS is

associated with osteoporosis in the affected limb. The bisphosphonate

pamidronate has been evaluated in placebo-controlled trials in this

population. Although long-term studies have not been conducted, short-term

evaluations indicate improvements in pain scores and overall disease severity.

Small but statistically significant improvements have been documented for this

intervention to improve physical functionality in patients.18

Therapy with calcitonin has also been evaluated in short-term, nonblinded

trials. Calcitonin combined with physical therapy was no better than physical

therapy alone in a two-month evaluation of pain scales, trophic changes, and

range of motion.19

The most common pharmacologic

therapies utilized for these patients are medications for neuropathic pain. As

with other interventions for CRPS, very little randomized or controlled data

exist to support their use. Many large neuropathic pain trials excluded

patients with CRPS. Most evidence to support their use is anecdotal.20

In a placebo-controlled trial evaluating gabapentin, pain scores improved

initially but returned to baseline. Sensory deficits, measured by monofilament

exams, improved in the gabapentin-treated groups. Patients in these groups

were significantly more likely to report dizziness and somnolence associated

with therapy.21

Trials involving patients with CRPS

are difficult to conduct. Enrollment is complicated by controversy regarding

the diagnostic criteria as well as the heterogeneous nature of the symptoms.

Evaluation of these trials is difficult because most do not value an

integrated or multidisciplinary care team. For a therapy to be considered

effective, it is generally accepted that pain scores should improve at least

50%,22 a degree of improvement rarely documented in interventions

evaluating one type of therapy.

Two interventions have shown

promise. The first was demonstrated in stroke patients, in whom occupational

and physical therapy initiated in the first two to three days after stroke

reduced the risk of developing CRPS. Administration of 500 mg of vitamin C for

50 days after wrist fracture and immobilization reduced the incidence of CRPS

from 22% to 7% in a placebo-controlled evaluation.23

Complex regional pain syndrome

is a debilitating disorder involving a sustained pain response after nerve

injury. Successful therapy for the disorder should include pharmacologic as

well as nonpharmacologic interventions aimed at returning the patient to a

functional status.

REFERENCES

1. Grabow TS, Christo PJ, Raja SN. Complex regional pain syndrome: diagnostic controversies, psychological dysfunction, and emerging concepts. Adv Psychosom Med. 2004;25:89-101.

2. Ghai B, Durega GP. Complex regional pain syndrome: a review. J Postgrad Med. October-December 2004;50:300-307.

3. Birklein F. Complex regional pain syndrome. J Neurol. 2005;252:131-138.

4. Frettloh J, Huppe M, Maier C. Severity and specificity of neglect-like symptoms in patients with complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) compared to chronic limb pain of other origins. Pain. 2006;124:184-189.

5. Veldman PH, Reynen HM, Arntz IE, et al. Signs and symptoms of reflex sympathetic dystrophy: prospective study of 829 patients. Lancet. 1993;342:1012-1016.

6. Kemler MA, Furnee CA. The impact of chronic pain on life in the household. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;23:433-441.

7. Pearce JM. Chronic regional pain and chronic pain syndromes. Spinal Cor. 2005;43:263-268.

8. Bruehl S, Chung OY. Psychological and behavioral aspects of complex regional pain syndrome management. Clin J Pain.2006;22:430-437.

9. Birklein F, Hanwerker HO. Complex regional pain syndrome: how to resolve the complexity? Pain. 2001;94:1-6.

10. Bruehl S, Carlson CR. Predisposing psychological factors in the development of reflex sympathetic dystrophy. Clin J Pain. 1992;49:337-347.

11. Lynch ME. Psychological aspects of reflex symptathetic dystrophy: a review of the adult and paediatric literature. Pain. 1992;49:337-347.

12. Harden RN, Swan M, King A, et al. Treatment of complex regional pain syndrome: functional restoration. Clin J Pain. 2006;22:420-424.

13. Birklein F, Reidle B, Sieweke N, et al. Neurological findings in complex regional pain syndromes--analysis of 145 cases. Acta Neurol Scand. 2000;101:262-269.

14. Morley S, Eccleston C, Williams A. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of cognitive behavior therapy and behavior therapy for chronic pain in adults, excluding headache. Pain. 1999;80:1-13.

15. Taskaynatan MA, Ozgul A, Tan AK, et al. Bier block with methylprednisolone and lidocaine in CRPS type I: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study. Reg Anesth Pain Med . 2004;29:408-412.

16. Christensen K, Jensen EM, Noer I. The reflex dystrophy syndrome response to treatment with systemic corticosteroids. Acta Chir Scan. 1982;148:653-655.

17. Kalita J, Vajpayee A, Misra UK. Comparison of prednisolone with piroxicam in complex regional pain syndrome following stroke: a randomized controlled trial. QJM. 2006;99:89-95.

18. Robinson JN, Sandom J, Chapman PT. Efficacy of pamidronate in complex regional pain syndrome type I. Pain Med. 2004;5:276-280.

19. Sahin F, Yilmaz F, Kotevoglu N, et al. Efficacy of salmon calcitonin in complex regional pain syndrome (Type I) in addition to physical therapy. Clin Rheumatol. 2006;25:143-148.

20. Rowbotham MC. Pharmacologic management of complex regional pain syndrome. Clin J Pain. 2006;22:425-429.

21. van de Vusse AC, Stomp-van den Berg SG, Kessels A, et al. Ranomised controlled trial of gabapentin in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome type I. BMC Neurol. 2004;4:13.

22. Forouzanfar T, Weber WE, Kemler M, et al. What is a meaningful pain reduction in patients with complex regional pain syndrome type I. Clin J Pain. 2003;19:281-285.

23. Quisel A, Gill JM, Witherell P.

Complex regional pain syndrome: which treatments show promise? J Fam Prac

. 2005;54:599-603.

To comment on this article, contact

[email protected].