Kids and Contacts

By Linda Conlin, ABOC, NCLEC

Release Date: February, 2013

Expiration Date: September 28, 2017

Learning Objectives:

Upon completion of this course, the participant should be able to:

- Identify common vision conditions in young children.

- Understand special considerations for fitting infants and children with contact lenses versus older patients.

- Understand evaluation techniques, instrumentation and the role of caregivers in pediatric contact lens fits.

Faculty/Editorial Board:

With over 30 years of experience and licensed in Connecticut, Massachusetts and Rhode Island, Linda Conlin is a writer and lecturer for regional and national meetings. She is chair of the Connecticut Board of Examiners for Opticians and is a manager for OptiCare Eye Health and Vision Centers, a multidisciplinary ophthalmic practice in Connecticut.

With over 30 years of experience and licensed in Connecticut, Massachusetts and Rhode Island, Linda Conlin is a writer and lecturer for regional and national meetings. She is chair of the Connecticut Board of Examiners for Opticians and is a manager for OptiCare Eye Health and Vision Centers, a multidisciplinary ophthalmic practice in Connecticut.

Credit Statement:

This course is approved for one (1) hour of CE credit by the National Contact Lens Examiners (NCLE). Course CTWJM547-2.

The past two decades have seen a

marked increase in how often

eyecare professionals (ECPs) fit

children with contact lenses. ODs

and physicians prescribe contact lenses for

children more frequently partially because of

improvements and adaptations in the contact

lenses themselves. The other part is that kids need

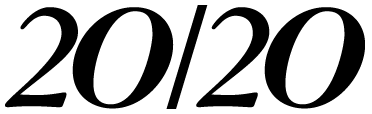

them. Six to nine percent of children younger than 18 have some type of vision condition. Amblyopia

accounts for five percent of that number. The

statistics, however, represent only the tip of

the pediatric vision care problem, and as

ECPs we should be concerned with a few

more. For example, 25 percent of school-age

children have vision problems. More than 11

percent of teenagers have undetected or

untreated vision problems. Mentally and

physically handicapped children have twice the incidence of vision problems as children

without disabilities.

The past two decades have seen a

marked increase in how often

eyecare professionals (ECPs) fit

children with contact lenses. ODs

and physicians prescribe contact lenses for

children more frequently partially because of

improvements and adaptations in the contact

lenses themselves. The other part is that kids need

them. Six to nine percent of children younger than 18 have some type of vision condition. Amblyopia

accounts for five percent of that number. The

statistics, however, represent only the tip of

the pediatric vision care problem, and as

ECPs we should be concerned with a few

more. For example, 25 percent of school-age

children have vision problems. More than 11

percent of teenagers have undetected or

untreated vision problems. Mentally and

physically handicapped children have twice the incidence of vision problems as children

without disabilities.

These statistics do not just represent fitting opportunities. They represent roadblocks that these children will face over their lifetimes if they do not receive vision correction at a young age. For example, statistics show that children with visual conditions frequently face additional challenges.

- More than 70 percent of juvenile offenders have undiagnosed vision problems.

- More than 50 percent of children who have a vision screening and are recommended to have an eye examination do not get one.

- Vision screenings detect only five percent of all vision problems.

- Twenty percent of school-age children have a learning disability.

- Seventy percent of those children have some form of visual impairment.

- In the youngest children, retinopathy of prematurity occurs in more than 16 percent of premature births.

- Astigmatism is present in 30 to 70 percent of children up to 2 years of age.

- In preschoolers, the incidence of ambly-opia is three to five percent and two to four percent for strabismus.

- Approximately one percent of 3-year-olds wear corrective lenses.

- Two percent of children entering first grade are myopic. (Fig. 1)

IDENTIFYING THE PROBLEM

Infants, very young children and some children with disabilities frequently do not respond to questions or cooperate well with the ECP during a typical eye exam and contact lens evaluation. At the same time, children usually become anx ious about procedures, so an ECP must be more flexible and creative when dealing with children.

Even though the child's parent will have supplied the history and chief complaint, the ECP must establish a rapport with the child. How? Reviewing the history and clarifying information with the parent before taking a young child into the exam room can help reduce stress. After all, he/she will spend what they may perceive to be a long time in a dark, perhaps scary room. Begin the evaluation while walking with the child to the exam room. Talk to the child about herself in a friendly manner and in a language she will understand. Look for obvious defects like nystagmus or strabismus and unusual posture or head tilt that may indicate vision problems.

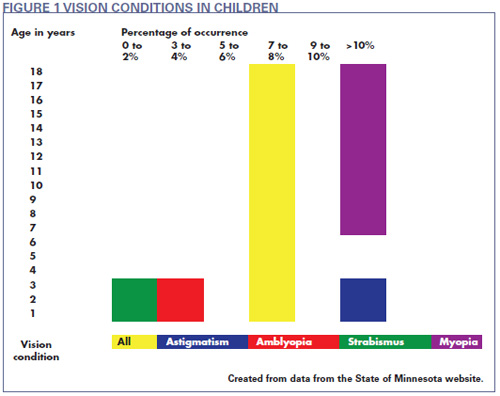

Ask the parent to hold a small child on his or her lap in the exam chair. Use instruments such as a handheld autore-fractor and keratometer while a parent holds the child. Make the process more like playtime and less like a clinical proce dure. For example, play "peekaboo" when you cover each eye with the occluder. Animated cartoons or mechanical toys with sound make excellent fixation targets for distance, while handheld toys work well for near. Play the "Match Game" with children who do not speak. Ask the child to match the Allen cards you or a parent show him to the same pictures on the distance screen (Fig. 2).

Children who are too young to match pictures can reach for a small object held at near and retrieve a toy they see across the room. Observe the way the child approaches the toy for more clues to vision problems. Teller acuity cards are another option. Because children prefer to look at patterns rather than solid color fields, the cards have a striped pattern on one half and are blank on the other. The stripes become progressively smaller, and the child will stop responding to the cards when he/she can no longer see the pattern.

For infants, observe their interest in looking at objects around them. Watch how they react to light, movement and color. The Bruckner test is another indicator of refractive error. Use a direct oph-thalmoscope to illuminate both pupils and observe the red reflex when light reflects from the retina. Inferior crescents indicate myopia and superior crescents indicate hyperopia.

The next step is to determine the prescription for corrective lenses. Streak retinoscopy works well for children who cannot respond to subjective tests. The practitioner flashes a light beam horizontally across the retina and observes the red reflex. The reflex moves either with or against the horizontal motion. Movement in the same direction as the light indicates the need for plus power, while movement in the opposite direction indicates minus power.

Instead of a phoroptor, use progressively stronger, handheld trial lenses of the indicated plus or minus power in front of the eye and repeat the test until the movement is neutralized. When corrected for working distance, the power that neutralized the movement becomes the prescription.

INFANTS IN CONTACT LENSES

Once you have a prescription, you can begin fitting the lenses. Let's start with a look at contact lenses for infants. Congenital cataracts occur in 1.7 of 10,000 births and can be bilateral or unilateral. Causes include genetics, metabolic disorders, birth trauma and maternal infection during pregnancy. Unlike their use in adults, intra-ocular lens implants in infants to replace the crystalline lens is controversial.

Eyeglasses on infants are impractical, which makes contact lenses the most common correction for pediatric aphakia. Because the first year of life is critical to visual development, ECPs usually fit contact lenses seven to 10 days after surgery, with soft lenses as the most common solution to restore phakic vision. Keeping in mind that a new baby's world is close; add 2D to 3D to the final prescription to enhance near vision. Avoid tight-fitting lenses because the child will spend a great deal of time sleeping with them.

Fitting infants with contact lenses for any vision problem presents some logisti cal challenges. Infants cannot be told to sit still or look at a target. They do, however, respond to voice recognition, touch and smell. Try to spend some time holding and speaking softly to the baby before beginning the fitting procedures. Instead of a slit lamp, use a penlight and magnifier or a lighted magnifier to evaluate the lens. Work quickly when inserting and removing the lens to help keep the child calm. Remember that this is an emotional time for parents who may react poorly to the baby's cries.

Make sure the parents understand the importance of follow-up exams. Generally, a follow-up visit is scheduled for 24 hours after the initial lens insertion, then every one to two weeks afterward for lens removal, cleaning and disinfection. Parents must know how to apply lens lubricant every morning and night.

After about four to six weeks, instruct the parents in lens care, insertion and removal. Advise parents to look for redness, discharge and the infant rubbing or reaching for his eyes. Show parents how to identify a decentered lens and the methods to recenter it. Provide them with written information on key points and a 24-hour phone number for assistance.

Whenever possible, provide a spare pair of lenses. Subsequent follow-up visits depend on specific medical issues, but keep in mind that the corneal curvature quickly becomes flatter during the first year and may require one or more base curve changes from the original fit.

CONTACT LENS PROCEDURES FOR YOUNG CHILDREN

Contact lenses frequently are a good choice for correcting vision in young children. In correction following surgery for congenital cataracts and in aniseikonia, contact lenses reduce differences in image size between eyes and improve peripheral vision. In amblyopia, an occluder or opaque contact lens is preferable to a patch because it's easier to keep in place. In fact, contact lenses solve the problem for parents who have to keep glasses clean, comfortable and in place for many children who need vision correction.

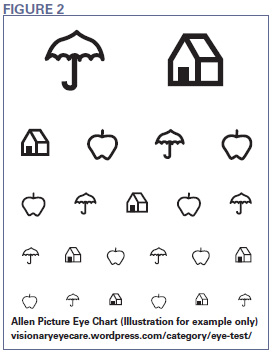

As with the eye exam, be flexible and creative with fitting procedures. Handheld keratometers reduce the difficulty in obtaining corneal curvature readings. When children are too young even for a handheld keratometer, the Bascom Palmer averages of corneal curvature provide a good starting point. The averages are based on age, ranging from birth to 9 years (Fig. 3).

If a child is too young to be held in a parent's lap for slit lamp evaluation, use a portable slit lamp. In the absence of corneal issues, a penlight and handheld magnifier or a lighted magnifier may also suffice for precorneal and lens evaluation. Usually, the practitioner will need to hold the child's eyelids open. If necessary, use a Burton lamp with the cobalt filter for fluorescein evaluation.

Older children present different challenges. They may have anxiety about the procedures and can be quite good at resisting them. A sympathetic, reassuring approach will help, but avoid being condescending. Explain what will happen in simple terms. Don't fudge or fib.

Remove the mystery surrounding a contact lens by letting the child hold and touch a disposable trial lens. It may be helpful to demonstrate some procedures, such as lens insertion or instrumentation, on a doll or teddy bear. Praise the child every time she cooperates. Avoid disapproval when she doesn't. Find another approach and ask the child for help by asking her how she wants to accomplish the task. This may provide an idea for a different task and reassures the child by involving her. You might have to ask the parent to swaddle a child who is completely uncooperative. But remember this is a step of last resort. You may be able to keep the child from moving, but you can bet she will scream and cry.

HANDLE WITH CARE

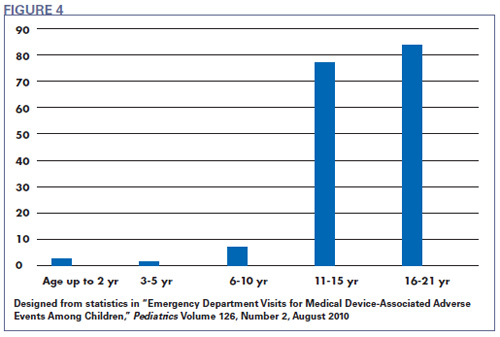

As with adult contact lens fits, pediatric contact lens fitting has risks. A study reported in Pediatrics magazine reviewed hospital emergency department visits (ED) associated with medical device-associated adverse events (MDAE). In 2004 and 2005, ophthalmology visits were the largest group of MDAEs for pediatric patients. Of those visits, contact lenses accounted for 23 percent of the MDAE cases, the largest group. Forty percent of all MDAEs for children 11 years of age and older were related to ophthalmic devices, and a majority of those cases involved contact lenses. Contact lens-related MDAEs included corneal abrasion, ulceration and conjunctivitis (Fig. 4).

ECPs must build a rapport with parents and their children regarding contact lens wear and to adequately educate everyone involved. Both children and parents must be motivated and have realistic expectations about wear, care and cost. Keep in mind that children may not complain about contact lens problems or may attempt to hide them because they are afraid they have done something wrong or that the lenses will be taken from them. Stressing the importance of follow-up visits with both parents and children, and scheduling the appointments in advance can minimize the risk of contact lens-related complications.

Fitting an older child of parents who wear contact lenses usually has the bonus of a positive attitude toward contact lens wear, eliminating the hurdle of explaining the benefits of contact lens wear versus the cost in time and money. But there can be a downside. The reality is that if Mom or Dad is noncompliant with contact lens wear and care, little Johnny will be too.

Don't take foreknowledge of contact lens wear for granted. Inform the parents and child about the treatment, risks, care and alternatives in the same way that you would for a patient entirely new to contact lenses. This is an opportunity to remind parents about the care they should be taking of their own lenses. It is possible that parents will recognize and correct their own noncompliant behaviors when they view them in light of the outcomes they want for their child.

THE FUTURE IS IN THEIR EYES

Technological advances in lens materials and easier care systems allow children to begin wearing contact lenses at younger ages. According to the American Opto-metric Association, studies have shown that contact lens wear improves the quality of life for many children not only by correcting vision, but also by improving self-confidence. According to the 576 optometrists who participated in the American Optometric Association (AOA) Research and Information Center Children & Contact Lenses study, 71 percent already prescribe lenses to children 10 to 12 years old, usually daily disposable lenses. Twenty-one percent said they are more likely to fit children 10 to 12 years old than they were a year ago. This means that ECPs must be ready for a larger, younger pediatric patient population. With parental support, new materials and easier care, the minimum age for fitting children with contact lenses is virtually nonexistent.

For all of its unique challenges, pediatric contact lens fitting comes with unique rewards. Eighty percent of early learning is visual, and as statistics show, uncorrected and undetected vision problems can have a long-term impact on a child's life. The most important investment we can make in our future is providing the best care and education for our children. Vision care is a critical part of that plan.